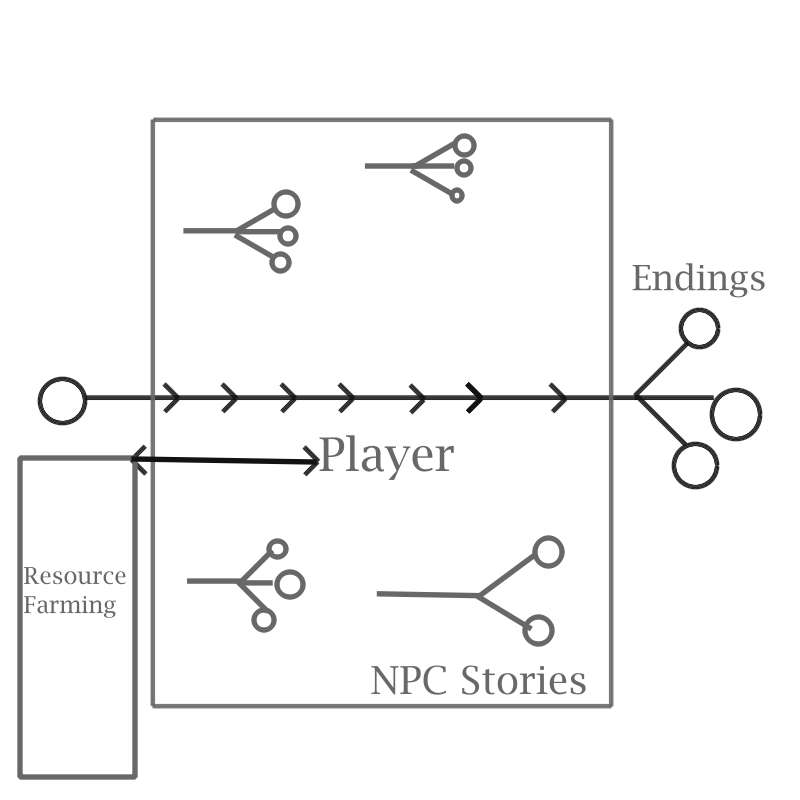

At its core The Matter of Being is a resource narrative. It abstracts certain complex narrative decisions through game mechanics, and makes the management of those abstractions the driver for producing narrative outcomes. One of the reasons I really like resource narratives, even if they’re heavily driven by writing, is that they can give players a more nuanced sense of agency than traditional branching fiction.

Take Sultan’s Game, for example. Like TMOB, Sultan’s Game is mostly words. Lots of important narrative decisions, however, can be executed by cards. Say you’ve been challenged to a duel and can appoint a champion. Instead of having a dozen different dialogues you can have with your followers about whether or not they’ll fight for you, you can simply drop a card into the “duel” slot. If you care about their survival, you can give them a sword or two.

It lets you tell all kinds of stories. Maybe you send someone you want to die. Maybe your last follower is your beloved wife, and you’re biting your nails about whether or not she can defend you in the court of battle. Sultan’s Game is full of moments like these, and writing tons of unique dialogue for every option would have been impossible.

There are downsides, of course. Suppose your beloved wife dies in battle. The actual moment of her death will be treated the same as everyone else’s, and maybe that feels a little weird. But it’s surprisingly easy to suspend that bit of disbelief, and you can remedy it quite well by having the game respond to her death if not specifically to her death in battle. I never let her die (Maggie #1), but it’s easy for me to imagine some cutscene in which her family is angry, or the protagonist becomes depressed. The how is usually less important than the outcome, which is preserved in a resource narrative.

There other downside, and the actual point of this article, is that you must actually contend with and plan around your Resources.

Unlike Sultan’s Game, TMOB has a lot of traditional dialogue. You can chat with people, ask them specific questions, and make a lot of your important narrative calls based on dialogue options that pop up in the moment. It’s still a resource narrative: you can befriend, murder, or matchmake anybody you like at the cost of energy or other resources, but I found it very tough to mentally reconcile these chunks of interactive fiction with the resource management tension I want to be part of the game.

At the time of writing this article, you could pretty much waltz through all 5 of my written quests without having to make any sacrifices. Not the plan! And it was quite hard to figure out how to fix it because TMOB, by its nature, has the potential to be very nonlinear. I can’t be certain which paths a player will take, which meant that any balancing of the game exceeded my limited mental capacity.

The Revelation!

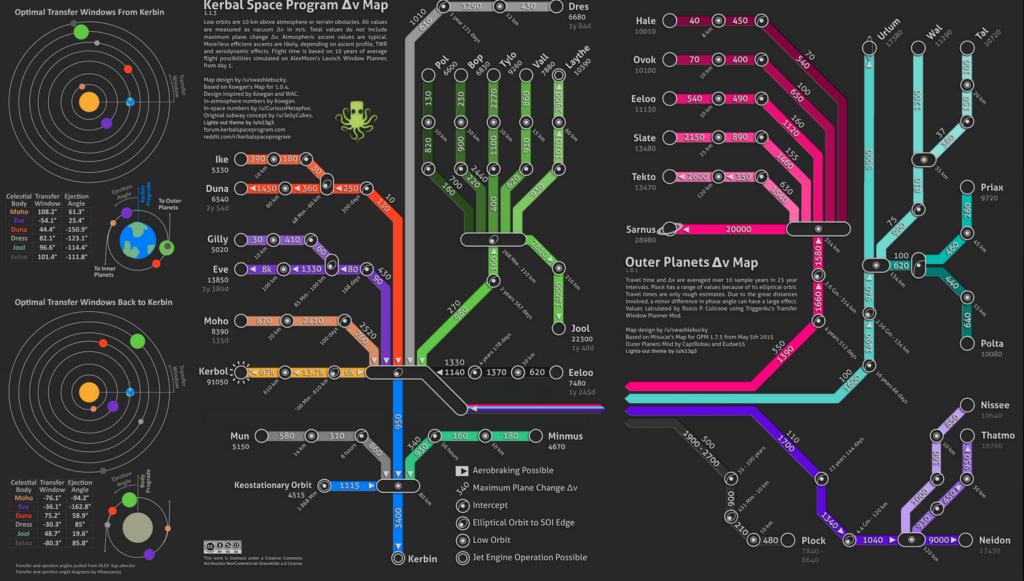

Faced with a conundrum I did as many artists before me: I fucked off and did something else. I played some Kerbal Space Program. Once I was ready to go to the moon I pulled up something called a “Delta-V Map”, which is a map of how much energy it takes to move between different bodies, and then I had to stop playing and get back to work because these little green men had somehow solved all of my problems.

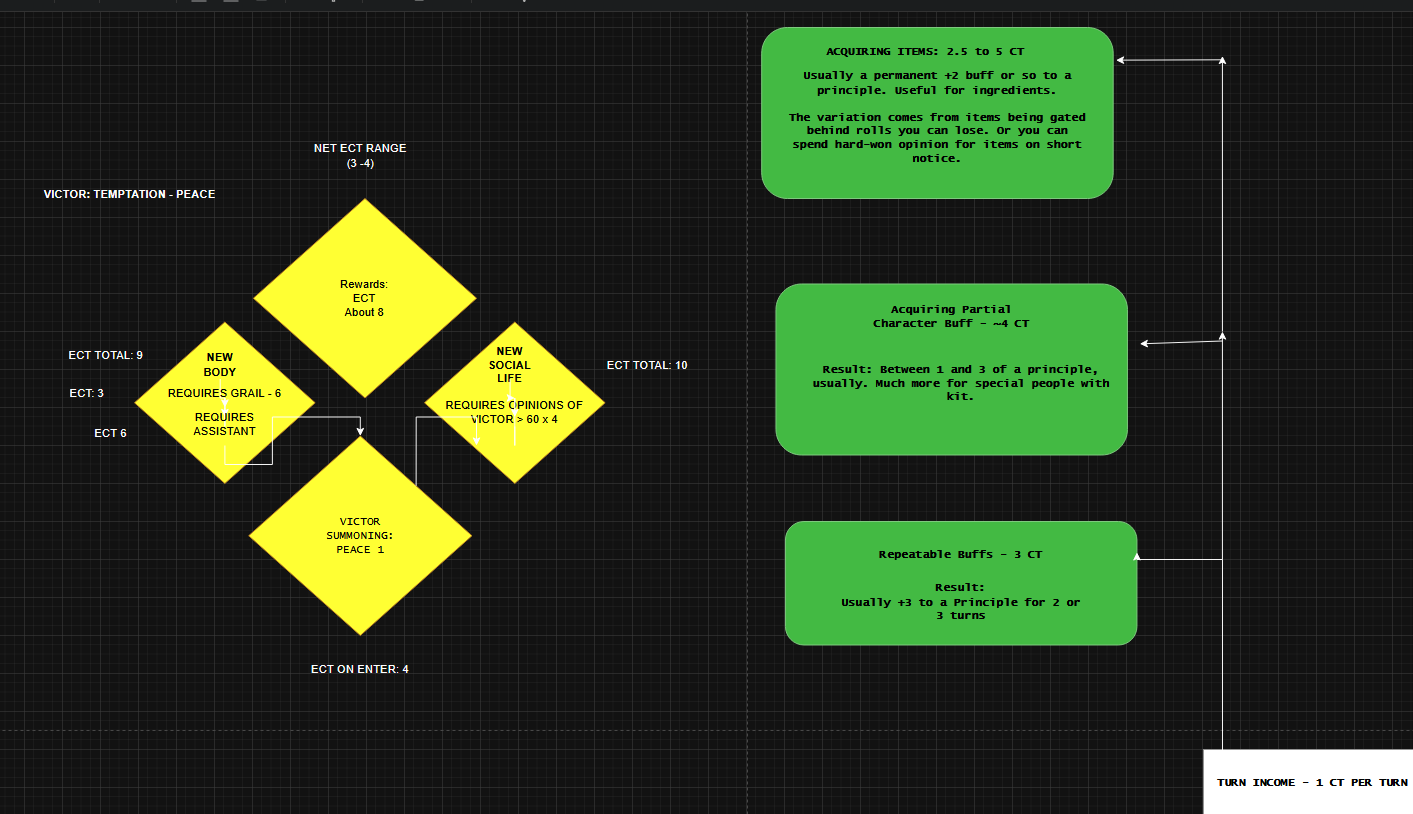

Delta-V maps don’t care about how you get your energy. They just tell you how much you need to move between points. If I could convert all of TMOB’s resources into some ‘base resource’, I could chart how much any given chunk of dialogue cost or profited the player. I decided that the base resource for TMOB was the ‘turn’. Accepting quests gives you turns, you use turns to get resources, and you use resources to solve problems. By calculating the approximate value of resources in terms of turns, I could make statements like “restoring Mohammed’s youth without killing anyone will cost around 6 to 7 turns.”

A Delta-V map developed by people with great aesthetic sense.I did this for a few quests, and I was frankly irritated at how useful the exercise was. I don’t really enjoy organizing, charting, or sorting things, but I kept at it because the process immediately revealed some flaws in my game design: Almost all of my quests were a guaranteed net-positive for turns, getting items was massively more expensive than I expected, temporary stat buffs were too powerful, and so on.

The main tension in TMOB is less about “trying not to lose the game”, as in Sultan’s Game, but basically to about “picking favorites.” If you want certain characters to get certain outcomes, you’ll have to do it at the expense of other characters. To make this happen I have to be willing to create stories that put the player “behind” in terms of resources. That’s not my instinct — I don’t really get off on restricting the player — but having actual numbers attached to things helps me confront the facts and institute an economy.

Now I can look at my charts and simulate playthroughs without having to go through all of my parallel dialogue. I can ask questions like: “Can the player make Mohammed young, keep Dr. Freeman from ascending, exhume Annette’s Wife, and help Victor ascend at the same time?” Maybe, but only if they let the Intercessors get to Gale and eat a member of Mohammed’s family.

It won’t be perfect, and I don’t need it to be, but it was a useful enough exercise that I thought I would share it here. Let me know if you try this approach! I’d love to hear about it on Discord @BluntBSE